Dianne Reeves |

|

Story by Jean Timmons  But that's about as far as that analogy went, even though she maintained her seated position throughout most of the performance. To the contrary, it was a masterful and quite polished performance that I shall not soon forget. But that's about as far as that analogy went, even though she maintained her seated position throughout most of the performance. To the contrary, it was a masterful and quite polished performance that I shall not soon forget. Over the past year, Reeves toured with the two guitarists for Europe's Jazz Baltica Festival. And from the stage, Reeves commented that her collaboration with Brazilian guitarist Romero Lubambo extended beyond that tour, which itself included twenty-five dates. The extent of trio work together was well reflected in the music that Friday evening in October. The generous and savvy leader gave time to both her accompanists to solo during the evening. And Malone helped her to bring the house down in a blues-tinged number that had the audience reciting Ee-ah-yae enthusiastically near the conclusion.

Reeves is a jazz singer who has gotten deserving breaks, for example, the tutelage of her cousin George Duke, but who has put in the work. She has done her share of woodshedding. As some will certainly recall, George Duke, master of keyboards, synthesizer, and composing, e.g., on such works as Miles Davis' Tutu and Amandla, worked as well as with Frank Zappa (for me, edging afield of jazz, surprising), produced a couple Reeves recordings that launched her career.

As most of the audience, I was taken aback by Reeves and the strings performing the Jobim piece, "Once I Loved." Initiated by that Brazilian tone of Lubambo, Reeves's interpretation was so very poignant and wise. She captured well the haunting of love gone. And then, at another juncture, pointedly appreciating her mother’s guidance, she celebrates the wisdom of all our elders with a relaxed and sweet "Today Will Be a Good Day." And she recalled her outstanding performance in George Clooney's Goodnight and Good Luck. Clooney incorporated Reeves into the film by inserting the role of a jazz program as part of the screen broadcast; and the center of the jazz was Reeves. In that film, I began to form a greater respect for Dianne Reeves, the jazz singer. She was captivating, while adding a nuance to the film that was badly needed. Reeves shared a nice anecdote with us about meeting, it seems, the greatest influence on her work, Sarah Vaughan. It was a charming anecdote, because it provided insight on what others thought of the incomparable diva. One of the musicians, according to Reeves, reminded Vaughan that it was time to go on stage. He called her "Sass," and it shook me up. On stage, behind stage, Sarah was who she was. Anyway, of all the jazz singers working today, Dee Dee Bridgewater moves me the most. She can do so many things. But on that October evening, I saw something in Reeves. Bridgewater is quite an athlete; but Reeves, like Sass, is a dancer, but with moves that can be so intricate that they can go unnoticed.

|

Romero Lumbabo |

Dianne Reeves |

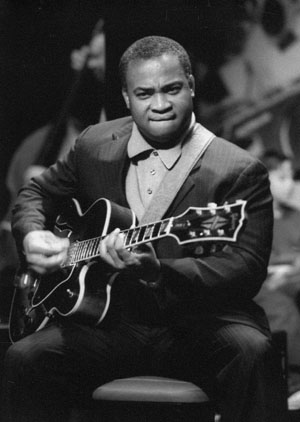

Russell Malone Photo by Mark Sheldon |