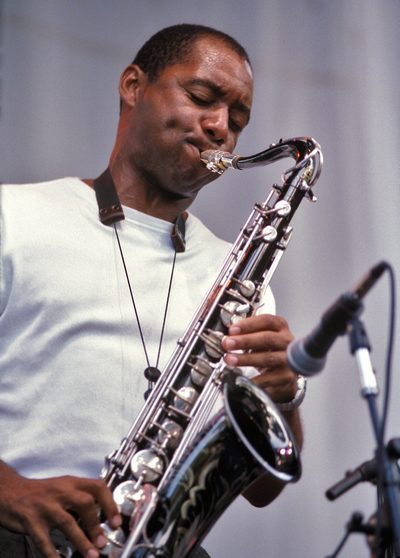

Branford Marsalis |

Joshua Redman |

|

Story by Jean Timmons Just the pairing of these two great saxophonists was momentous to many aficionados of the music. In Jean Bach's film A Great Day in Harlem, Nat Hentoff, iconoclastic jazz critic, passed on his wife Margot's estimation that musicians such as Charles Mingus, Lester Young, and Billie Holiday were "as much literary as musical figures - like larger-than-life characters in a novel." In that regard, Redman at 39 and Marsalis at 47 are literary figures, too. Redman's father is the legendary Dewey Redman; his Russian mother, Renee Schedroff, was a dancer. He graduated summa cum laude from Harvard and turned down the opportunity to study law at Yale to become a jazz musician. After winning the Thelonious Monk competition in 1991, he has made much music but continues to grow and experiment. In 2004, he was a founder of the SF Jazz Collective, a gathering of eight exceptional jazz musicians who meet for many weeks during the year to work exclusively on the goals of the collective, which is to showcase and extend modern jazz. Amazingly his stage presence is still modest; he is not one who suffers from hubris. As for Branford Marsalis, musical versatility is his calling card - to the chagrin of brother Wynton, who, under the tutelage of one Stanley Crouch, has decreed that there is only one "real jazz." Playing and touring with Sting certainly irritated, to put it mildly, both Wynton and Crouch. Contemporary pop music with his band Buckshot LeFonque is a curiosity to even the more tolerant jazz fan. Yet Branford seems undeterred from exploring as many facets of life and music as he can. He has acted in films, including Throw Mama from the Train, and for two years in the 1990s was musical director of The Tonight Show with Jay Leno. The stage is set.  Naturally, Redman initiated the evening with the trio only. The first selection was an original Redman composition, inspired by drummer Hutchinson,"Hutch Hiker's Guide." When he plays, Redman is perpetual motion, mainly a little hitching up of his leg and tapping his feet to the beat. Sometimes hitching the right leg, sometimes the left. And he scoots. The "Guide" was a fine introduction to the members of the trio, for each took engaging solos. "East of the Sun (and West of the Moon)" opened with a bluesy solo by Redman. He recorded the song on his Back East CD and lived up to that standard in this concert. After that wailing blues opening, the melody was asserted and with the entrance of drums and bass came this Latin-like rhythm. Each musician followed his improvisation. It was very uptempo as it progressed but not cacophonous, which was impressive. At one point Redman was off in Sonny Rollins land. When they come back to the melody, Joshua played even prettier. Bass and drum were simpatico. The ending was a ride back and forth between drum and saxophone with the drumming growing more intense as Redman vocally spurred the drummer on. It was reminiscent of Trane and Jones. One is reminded that in his youth Redman recorded with Elvin Jones. Redman opened "Zarafah," his original composition dedicated to his mother, on soprano sax. (His soprano sounded, to my ears, a bit like a clarinet, which, incidentally was his first instrument.) The music reflects a Middle Eastern accent, perhaps influenced by the music he heard when his mother took him to see Indian dance and to listen to Indian music in Berkeley. His solo did not seem improvised; it was a very structured piece. Initially it was shrill in its chant-like admonition. The bass enters, then the drums, and with their entrance the music relaxes. The shrill opening, the admonishment, became a sweet conversation. The music developed a sway that dissolved into strong bass work, a calming response to the soprano voicing. In the solos of his sidemen, Redman added little touches of music, in the fashion of Count's piano notes that encouraged the solos of his players. It was a long, very complex and exciting piece. With "Soul Dance" (another Redman composition), he switched to the tenor. This version of "Soul Dance," which was recorded on his Wish CD, is well suited to a trio treatment. And Redman appeared to be dancing, dancing and grunting, leaning back occasional as if to better propel himself for the next onslaught. Indeed, hubris or not, it is very difficult to watch the other musicians on stage when he is off on a tear. It had a great ending; so much so that one was beginning to fear that Marsalis would just ruin the performance when he arrived.  On the very next selection, Redman and Hutchinson were into their Coltrane/Hayes routine, and it was difficult to tell who was driving whom. When suddenly, enter Marsalis and the audience roared. Branford has a heavier sounding horn - but it offered a great contrast. Then we had two sharply dressed men, blowing away, and both bouncing up and down. The bass jumped in without difficult, but seemingly the drummer had difficulty incorporating the sounds of the additional player. (Interesting that the composition itself is a Branford effort, "Citizen Tain," after his own long-time drummer Jeff "Tain" Watts.) It was like too much drumming. Did Marsalis break the continuity? Then Branford and Redman faced each other, as though engaging in the traditional cutting session, both moving back and forth with the effort. Miraculously, there was the sudden hint of something very special in that hall. The hint became reality on the next Redman composition, "Mantra # 5" from the Back East CD, which began with a soprano sax duet, picked up by the drum and bass before the sopranos return. Branford is known for his ease and assurance with a difficult instrument to master. Both musicians displayed mastery with music perfectly suited to the soprano and to their unique sounds: Redman slightly airy; Branford slightly mellow. These voicing were shown off to great effect as the two took multiple solos, back and forth. It was almost a cutting session, because it was so civilized. It was great. My companero whispered that this was not "Kenny G territory." Here, too, the drummer was back to being an integral part of the performance, punctuating the ending with real nice playing. As if to accentuate the "cutting" aspect of their performance, they took on "Blues Up and Down" at breakneck speed. This is a composition made famous by such tenor saxophonists as Gene Ammons, Sonny Stitt, and Johnny Griffin - it has a long history. But Redman's solo was more in the vein of the other Sonny, Rollins; while Branford, taking the calmer turn, was like Stitt. Meanwhile the drummer kept coming at Branford, who held up under the onslaught. As for the bass, it was in the background, keeping a steady pulse. When it was Grenadier's turn, he took full advantage and made his bass sing. Very great spirit in the playing of an old chestnut. At the end, the saxophonists seemed to play even faster: one played, then the other, and then together. No mistaking the cutting intent here. The crowd burst into applause. When they left the stage, we knew they would return for an encore. The music had ended much too soon. So they came back and Joshua opened with beautiful music before announcing the theme of "Body and Soul." On this one, the two complemented each other, as if to heal any wounds either might have sustained in those cutting sessions. When they included, what I call, Dexter's allusive line, "I know you'd be mine again," it took a lot to resist the urge to lend them some of his greatness. But why do that? They are still in the process of creating their own legacies. And part of their legacies may well be the fact that these two literary figures, with a superlative cast, faced off one night at Symphony Center and proved to all present that on saxophone today they are unparalleled. |